Lie group and lie algebra for robotics

Table of Contents

- Vectors

- Euclidean Transformations

- Rotation Representations

- Homogeneous Transformations

- Rotational Kinematics

- Translation

- Lie Groups

- Lie Algebras

- Exponential and Logarithm Maps

- Adjoint Representation

Rigid Body Motion in 3D Space

How is the motion of a rigid body in three-dimensional space described?

This question is fundamental because when we describe the pose of a robot, we are essentially describing the motion of a rigid body in 3D. Moreover, in robotics we often need to estimate and optimize this pose. The way we represent the pose directly determines the form of the robot’s motion equations and optimization equations.

In 3D space, rigid body motion can be expressed using two concepts:

- Translation, which is straightforward and usually represented by a displacement vector.

- Rotation, which can be represented in multiple ways, each with advantages and drawbacks.

1. Vectors

A vector is a physical entity in space, independent of scalar values.

To describe a vector, we must specify a coordinate frame and its basis vectors $[\mathbf{e}_1, \mathbf{e}_2, \mathbf{e}_3]$.

A vector $\mathbf{a}$ in this frame can be written as:

Thus, vector coordinates depend both on the vector itself and the chosen coordinate system.

1.1 Vector Operations

Two key operations are dot product and cross product:

- Dot product:

- Cross product:

where $\mathbf{a}^\wedge$ denotes the skew-symmetric matrix form of $\mathbf{a}$.

The cross product result is a vector perpendicular to both $\mathbf{a}$ and $\mathbf{b}$, with magnitude

$|\mathbf{a}||\mathbf{b}|\sin\langle\mathbf{a}, \mathbf{b}\rangle$.

It also encodes the idea of a rotation axis, linking to later descriptions of rotation.

2. Euclidean Transformations

Suppose we have two coordinate frames:

- A world frame (inertial), e.g., fixed at a wall corner.

- A robot frame, moving with the robot.

A point $\mathbf{p}$ exists physically, but has different coordinates in each frame. The mapping between the two coordinate representations is a Euclidean transformation.

Rigid body motion preserves vector length and direction, so the transformation consists of:

- a rotation, and

- a translation.

3. Rotation Representations

3.1 Rotation Matrix

Consider a vector $\mathbf{p}$ in two frames:

\[[\mathbf{e}_1, \mathbf{e}_2, \mathbf{e}_3] \begin{bmatrix} a_1 \\ a_2 \\ a_3 \end{bmatrix} = [\mathbf{e}_1', \mathbf{e}_2', \mathbf{e}_3'] \begin{bmatrix} a_1' \\ a_2' \\ a_3' \end{bmatrix}\]Left multiplying by $[\mathbf{e}_1^T, \mathbf{e}_2^T, \mathbf{e}_3^T]^T$ gives:

\[\mathbf{a} = \mathbf{R}\mathbf{a}'\]where $\mathbf{R}$ is the rotation matrix formed from inner products of the bases.

$\mathbf{R}$ is an orthogonal matrix with determinant $+1$, i.e.,

This set is called the Special Orthogonal Group.

3.2 Rotation Vector

Rotation matrices have redundancy (9 elements, 3 DOF, with constraints).

A more compact 3-parameter representation is the rotation vector:

- Direction = rotation axis $n$

- Magnitude = rotation angle $\theta$

So the rotation vector is $\theta n$.

The conversion with rotation matrices uses Rodrigues’ formula:

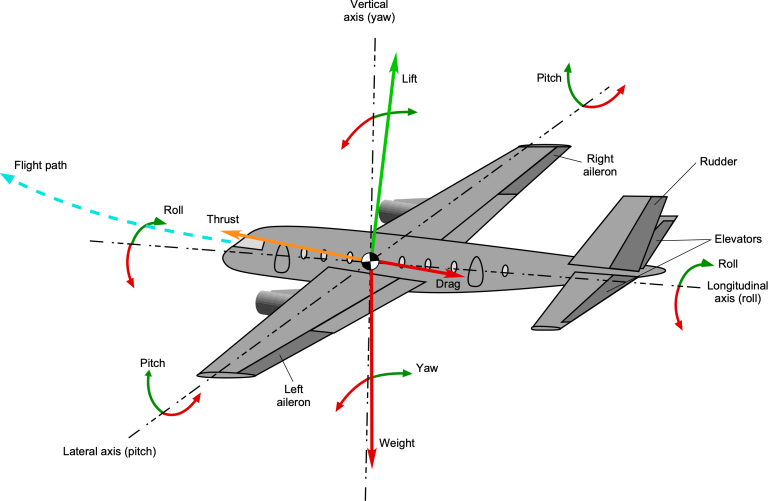

\[\mathbf{R} = \cos \theta \mathbf{I} + (1-\cos\theta)n \dot n^T + \sin\theta \mathbf{n}^\wedge\]3.3 Euler Angles

A rotation can also be decomposed into three successive rotations about axes.

For example, in photogrammetry and robotics:

- Roll – Yaw – Pitch (1-2-3 or X-Y-Z sequence).

- The full rotation is the product of the three basic rotation matrices.

Euler angles are intuitive but suffer from singularities (gimbal lock).

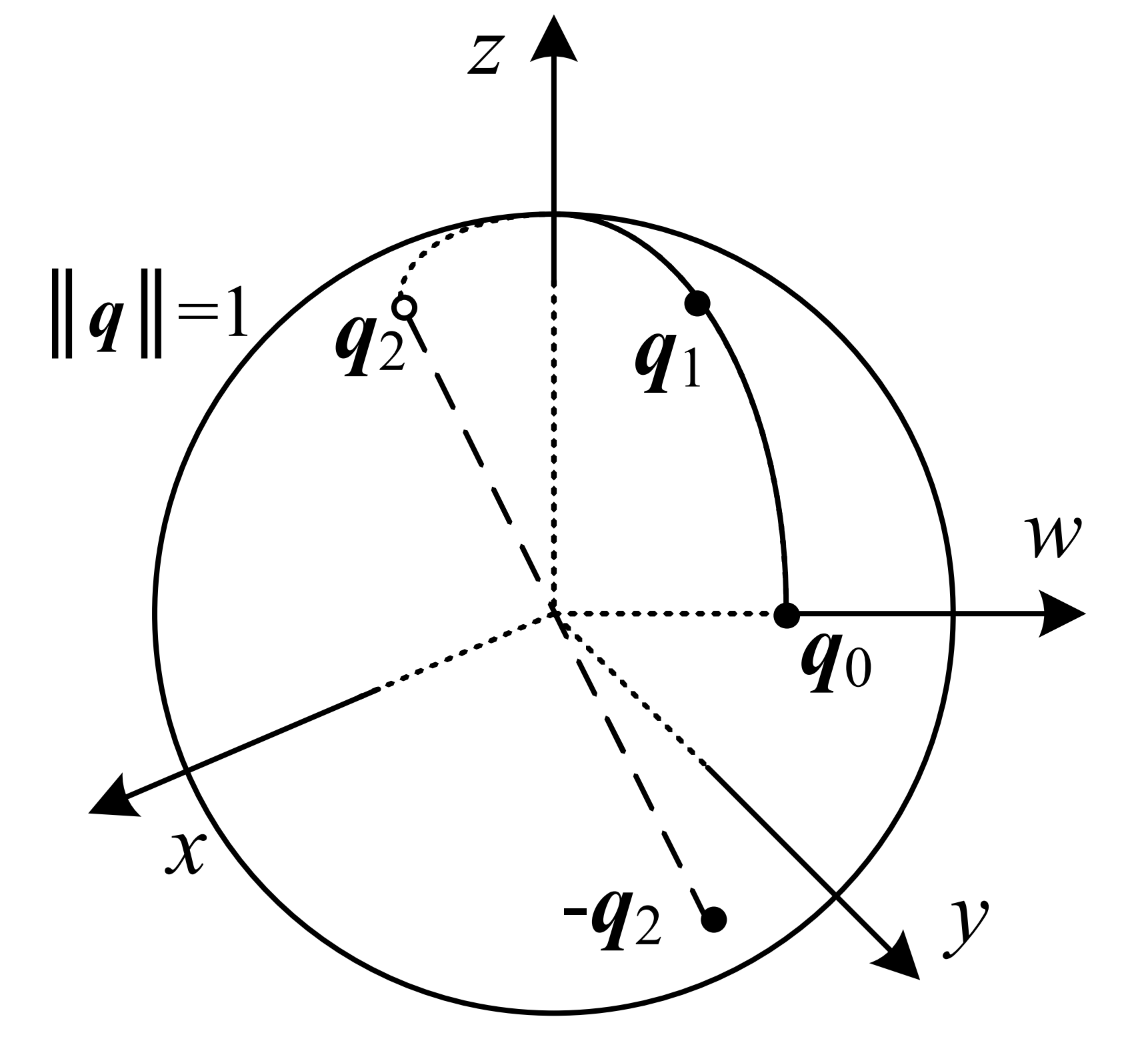

3.4 Quaternions

Euler angles and rotation vectors have singularities.

Quaternions provide a compact, non-singular representation.

A quaternion is defined as:

\[\mathbf{q} = q_0 + q_1 i + q_2 j + q_3 k = [s, \mathbf{v}]\]where $s$ is the scalar part, and $\mathbf{v}=[q_1, q_2, q_3]^T$ is the vector part.

Unit Quaternion Representation of Rotation

For a rotation of angle $\theta$ around axis $\mathbf{n}$:

\[\mathbf{q} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos \tfrac{\theta}{2} \\ n_x \sin \tfrac{\theta}{2} \\ n_y \sin \tfrac{\theta}{2} \\ n_z \sin \tfrac{\theta}{2} \end{bmatrix}\]The corresponding rotation matrix is:

\[\mathbf{R}= \begin{bmatrix} 1 - 2q_2^2 - 2q_3^2 & 2q_1q_2 - 2q_0q_3 & 2q_1q_3+2q_0q_2 \\ 2q_1q_2 + 2q_0q_3 & 1 - 2q_1^2 - 2q_3^2 & 2q_2q_3 - 2q_0q_1 \\ 2q_1q_3 - 2q_0q_2 & 2q_2q_3 + 2q_0q_1 & 1 - 2q_1^2 - 2q_2^2 \end{bmatrix}\]Quaternion Operations

-

Addition:

$\mathbf{q}_a \pm \mathbf{q}_b = [s_a \pm s_b, \; \mathbf{v}_a \pm \mathbf{v}_b]$ -

Multiplication:

$\mathbf{q}_a \mathbf{q}_b = [s_as_b - \mathbf{v}_a^T\mathbf{v}_b,\; s_a\mathbf{v}_b+s_b\mathbf{v}_a+\mathbf{v}_a\times\mathbf{v}_b]$ -

Conjugate:

$\mathbf{q}^* = [s, -\mathbf{v}]$ -

Inverse:

$\mathbf{q}^{-1} = \mathbf{q}^*/|\mathbf{q}|$ -

Rotation of a vector $\mathbf{p}=[0,\mathbf{v}]$:

$\mathbf{p}’ = \mathbf{q}\mathbf{p}\mathbf{q}^{-1}$

4. Homogeneous Transformations

With both rotation ($\mathbf{R}$) and translation ($\mathbf{t}$), the transformation of a point is:

\[\mathbf{a}' = \mathbf{R}\mathbf{a} + \mathbf{t}\]To make this linear, we use homogeneous coordinates:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{a}' \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{R} & \mathbf{t} \\ \mathbf{0}^T & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{a} \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}\]The $4 \times 4$ matrix belongs to the Special Euclidean Group:

\[SE(3) = \left\{ \mathbf{T} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{R} & \mathbf{t} \\ \mathbf{0}^T & 1 \end{bmatrix} \;\middle|\; \mathbf{R}\in SO(3),\; \mathbf{t}\in\mathbb{R}^3 \right\}\]5. Rotational Kinematics

Assume frame $\mathbf{F}2$ rotates relative to $\mathbf{F}_1$ with angular velocity $\omega{21}$ (so $\omega_{12} = -\omega_{21}$).

The relationship between inertial and moving frame time derivatives:

\[\dot{\mathbf{r}} = \mathring{\mathbf{r}} + \omega_{21} \times \mathbf{r}\]5.1 Angular Velocity and Rotation Matrix

Poisson’s formula:

\[\dot{\mathbf{C}}_{21} = -[\omega_2^{21}]_\times \mathbf{C}_{21}\]and equivalently:

\[[\omega_2^{21}]_\times = -\dot{\mathbf{C}}_{21}\mathbf{C}_{21}^T\]5.2 Euler Angles Representation

For a 1-2-3 Euler sequence:

\[\omega_2^{21} = \mathbf{S}(\theta_2, \theta_3)\dot{\theta}\]where:

\[\mathbf{S}(\theta_2,\theta_3)= \begin{bmatrix} \cos \theta_2 \cos \theta_3 & \sin \theta_3 & 0 \\ -\cos \theta_2 \sin \theta_3 & \cos \theta_3 & 0 \\ \sin \theta_2 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\]and the inverse relation:

\[\dot{\theta} = \mathbf{S}^{-1}(\theta_2, \theta_3)\omega_2^{21}\]Note the singularity at $\theta_2=\pi/2$.

5.3 Perturbed Rotations

Rotations lie on the SO(3) group (non-commutative).

For perturbations, linearization is done in the tangent space.

For rotation matrix $\mathbf{C}(\bar{\theta}+\delta \theta)$:

\[\mathbf{C}(\bar{\theta}+\delta \theta) \approx (1 - [\delta\phi]_\times)\mathbf{C}(\bar{\theta})\]5.4 Perturbations in Euler Angles

For a rotation sequence $\alpha-\beta-\gamma$:

\[\frac{\partial \mathbf{C}(\theta)\mathbf{v}}{\partial \theta} = (\mathbf{C}(\theta)\mathbf{v})_\times \mathbf{S}(\theta_2,\theta_3)\]This yields Jacobians used in optimization and estimation.

6. Translation

For points:

\[\mathbf{r}^{pi} = \mathbf{r}^{pv} + \mathbf{r}^{vi}\]In inertial frame:

\[\mathbf{r}^{pi}_i = \mathbf{C}_{iv}\mathbf{r}^{pv}_v + \mathbf{r}^{vi}_i\]Homogeneous transformation:

\[\mathbf{T}_{iv} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{C}_{iv} & \mathbf{r}^{vi}_i \\ \mathbf{0}^T & 1 \end{bmatrix}\]Inverse:

\[\mathbf{T}_{vi} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{C}_{vi} & \mathbf{r}^{iv}_v \\ \mathbf{0}^T & 1 \end{bmatrix}\]7. Lie Groups

A group is a set $\mathcal{G}$ with a binary operation $\cdot$ such that:

- Closure: $a, b \in \mathcal{G} \implies a \cdot b \in \mathcal{G}$

- Associativity: $(a \cdot b)\cdot c = a \cdot (b \cdot c)$

- Identity: $\exists e \in \mathcal{G}$ such that $a \cdot e = e \cdot a = a$ for all $a$

- Inverse: For every $a \in \mathcal{G}$, there exists $a^{-1} \in \mathcal{G}$ such that $a \cdot a^{-1} = e$

A Lie group is a group that is also a smooth manifold, where group operations (multiplication and inverse) are smooth (differentiable) maps.

This dual structure allows us to combine algebraic properties (group theory) with geometric properties (manifold theory).

7.1 Manifolds

An $N$-dimensional manifold $\mathcal{M}$ is a geometric space that is locally Euclidean. For any point $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{M}$, there exists a neighborhood that is homeomorphic to $\mathbb{R}^N$.

-

Example 1: Quaternion manifold

A quaternion $\mathbf{q} = [x,y,z,w]$ represents 3D rotation only if $|\mathbf{q}|=1$.

The constraint $|\mathbf{q}|=1$ places $\mathbf{q}$ on the surface of a 4D sphere ($S^3$). -

Example 2: SE(3) manifold

An element of $SE(3)$ has 6 degrees of freedom (3 rotation + 3 translation).

Although the manifold cannot be visualized, locally it behaves like $\mathbb{R}^6$.

Smooth: A map $f$ from $U\subset R^m$ to $V \subset R^n$ is smooth if all partial derivatives of $f$, of all orders, exist and are continuous.

A group can act on another set or space.

If $a,b \in G$ and $v \in V$:

- Identity does nothing: $e \cdot v = v$

- Associativity holds: $(a b)\cdot v = a \cdot (b \cdot v)$

Example:

Let $R \in SO(3)$ and $p \in \mathbb{R}^3$. Then the action is

\(R \cdot p = Rp\)

which means the group $SO(3)$ acts on vectors in $\mathbb{R}^3$ via rotation.

At any point $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{M}$, the tangent space $\mathcal{T}_{\mathbf{x}}\mathcal{M}$ is a linear vector space that approximates the manifold locally.

- $SO(3)$: tangent space is 3D (angular velocity vectors)

- $SE(3)$: tangent space is 6D (linear + angular velocity vectors)

The tangent space at the identity element is called the Lie algebra.

- Lie algebra encodes infinitesimal motions.

- Notation:

- $\mathfrak{so}(3)$ for $SO(3)$

- $\mathfrak{se}(3)$ for $SE(3)$

7.2 SO(3): The Special Orthogonal Group

The set of valid 3D rotation matrices:

\[SO(3) = \{ C \in \mathbb{R}^{3\times 3} \;|\; C C^T = I, \det C = 1 \}\]- $C C^T = I$: orthogonality (columns are orthonormal basis vectors)

- $\det C = 1$: preserves orientation (no reflection)

- Only 3 degrees of freedom despite being a $3\times 3$ matrix

Thus, $SO(3)$ represents all possible orientations of a rigid body in 3D.

7.3 SE(3): The Special Euclidean Group

The set of rigid body transformations (rotation + translation):

\[SE(3) = \left\{ T = \begin{bmatrix} C & r \\ 0^T & 1 \end{bmatrix} \;\middle|\; C \in SO(3),\; r \in \mathbb{R}^3 \right\}\]Here:

- $C$ is a rotation matrix

- $r$ is a translation vector

- $T$ is a $4\times 4$ homogeneous transformation matrix

$SE(3)$ forms a Lie group with 6 degrees of freedom (3 for rotation, 3 for translation).

7.4 Application in Robotics

- Pose graph SLAM: solved in $se(3)$, mapped back to $SE(3)$

- Pose $(x,y,\theta)$ belongs to $SE(2)$

- Differential-drive/unicycle models evolve in $SE(2)$

- Mapping, localization (SLAM), and path planning are all naturally formulated in $SE(2)$

- EKF on SE(3): motion updates use $\oplus$, residuals use $\ominus$

- Adjoint matrices: transform twists between frames

- Optimization: unconstrained solvers via tangent space linearization

Key point: $SE(n)$ captures both the geometry (rotations + translations) and the algebra (group structure) of rigid motions.

7.5 Lie Group Calculus

If $f: \mathcal{M} \mapsto \mathcal{N}$ is a function between manifolds:

\[\mathbf{J} = \frac{Df(\mathbf{x})}{D\mathbf{x}} = \lim_{\tau \to 0} \frac{f(\mathbf{x}\oplus\tau)\ominus f(\mathbf{x})}{\tau}\]This defines Jacobians on manifolds.

On Lie groups, states are modeled with perturbations:

\[\mathbf{x} = \bar{\mathbf{x}} \oplus \tau, \quad \tau = \mathbf{x}\ominus \bar{\mathbf{x}}\]Covariance:

\[\mathbf{P}_{\mathbf{x}} = \mathbb{E}[\tau \tau^\top]\]Propagation:

\[\mathbf{P}_{\mathbf{y}} = \mathbf{J} \mathbf{P}_{\mathbf{x}} \mathbf{J}^\top\]8. Lie Algebras

Every Lie group has an associated Lie algebra, which is its tangent space at the identity.

Intuitively:

- The Lie group describes finite motions (global transformations).

- The Lie algebra describes infinitesimal motions (velocities, twists).

Formally, a Lie algebra $(\mathfrak{g}, [\cdot,\cdot])$ is:

- A vector space $\mathfrak{g}$

- Equipped with the Lie bracket $[X,Y] = XY - YX$ (matrix commutator)

-

Properties: closure, bilinearity, antisymmetry, Jacobi identity

-

Plus ($\oplus$):

\(\mathbf{x} \oplus \tau := \mathbf{x} \cdot \exp(\tau)\) - Minus ($\ominus$):

\(\mathbf{x}_2 \ominus \mathbf{x}_1 := \log(\mathbf{x}_1^{-1} \mathbf{x}_2)\)

These are used in optimization and SLAM residuals.

8.1 so(3): The Lie Algebra of SO(3)

\[so(3) = \{ \phi^\wedge \in \mathbb{R}^{3\times 3} \;|\; \phi \in \mathbb{R}^3 \}\]Here:

- $\phi \in \mathbb{R}^3$ is an axis-angle vector

- $\phi^\wedge$ is its skew-symmetric matrix:

The Lie bracket is the matrix commutator:

\[[\Phi_1, \Phi_2] = \Phi_1\Phi_2 - \Phi_2\Phi_1\]This corresponds to the cross product in $\mathbb{R}^3$: \([\phi_1^\wedge, \phi_2^\wedge] = (\phi_1 \times \phi_2)^\wedge\)

So $so(3)$ encodes angular velocities.

8.2 se(3): The Lie Algebra of SE(3)

\[se(3) = \left\{ \xi^\wedge = \begin{bmatrix} \phi^\wedge & \rho \\ 0^T & 0 \end{bmatrix} \;\middle|\; \rho,\phi \in \mathbb{R}^3 \right\}\]Here:

- $\rho$ = translational velocity

- $\phi$ = angular velocity

- $\xi = [\rho^T,\; \phi^T]^T \in \mathbb{R}^6$ is called a twist

The operator $\wedge$ maps a twist into its matrix form.

The operator $\vee$ (vee) maps it back to vector form.

Extended operator for adjoint:

\[\xi^\curlywedge = \begin{bmatrix} \phi^\wedge & \rho^\wedge \\ 0 & \phi^\wedge \end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{6\times 6}\]9. Exponential and Logarithm Maps

Lie algebras describe local motions, but we often need to move between local and global descriptions.

This is done with the exponential map and its inverse, the logarithm map.

- Exponential map: $\exp: \mathfrak{g} \mapsto G$

- Logarithm map: $\log: G \mapsto \mathfrak{g}$

These allow switching between Lie algebra (linear tangent space) and Lie group (nonlinear manifold).

9.1 Rotation (so(3) → SO(3))

Given $\phi = \theta a$, with $a$ a unit axis and $\theta$ an angle:

\[\exp(\phi^\wedge) = \cos\theta I + (1-\cos\theta)aa^T + \sin\theta a^\wedge\]This is Rodrigues’ formula.

It maps an axis-angle vector to a rotation matrix.

Inverse (log map):

\[\theta = \arccos\left(\frac{\mathrm{tr}(C)-1}{2}\right), \quad a = \frac{1}{2\sin\theta}\begin{bmatrix} C_{32}-C_{23}\\ C_{13}-C_{31}\\ C_{21}-C_{12}\end{bmatrix}\]9.2 Pose (se(3) → SE(3))

For $\xi = [\rho,\phi]$:

\[\exp(\xi^\wedge) = \begin{bmatrix} R & J\rho \\ 0^T & 1 \end{bmatrix}\]where $R = \exp(\phi^\wedge)$ and $J$ is the left Jacobian of SO(3):

\[J = \frac{\sin\theta}{\theta}I + \left(1-\frac{\sin\theta}{\theta}\right)aa^T + \frac{1-\cos\theta}{\theta} a^\wedge\]$J$ accounts for the coupling between translation and rotation.

If $\theta\to 0$, $J \to I$.

Inverse mapping (log): extract $\rho, \phi$ from $T \in SE(3)$.

9.3 Jacobian

The Jacobian and its inverse are important in optimization:

\[J^{-1} = \frac{\theta}{2}\cot\frac{\theta}{2} I + \left(1-\frac{\theta}{2}\cot\frac{\theta}{2}\right)aa^T - \frac{\theta}{2} a^\wedge\]If $\theta = 2k\pi$, $J$ is singular.

9.4 Direct Series Expansion

Using matrix identities, we can expand:

\[T = \exp(\xi^\wedge) = I + \xi^\wedge + \frac{1-\cos\phi}{\phi^2}(\xi^\wedge)^2 + \frac{\phi-\sin\phi}{\phi^3}(\xi^\wedge)^3\]This avoids computing infinite series explicitly.

10. Adjoint Representation

The adjoint describes how a transformation in $SE(3)$ maps twists between coordinate frames.

For $T = \begin{bmatrix} C & r \ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \in SE(3)$:

\[Ad(T) = \begin{bmatrix} C & r^\wedge C \\ 0 & C \end{bmatrix}\]This means:

- The linear velocity part rotates by $C$ and is shifted by $r$

- The angular velocity part rotates by $C$ only

For the algebra:

\[ad(\xi) = \xi^\curlywedge = \begin{bmatrix} \phi^\wedge & \rho^\wedge \\ 0 & \phi^\wedge \end{bmatrix}\]Relationship between group and algebra adjoints:

\[Ad(\exp(\xi^\wedge)) = \exp(ad(\xi))\]Robotics meaning:

- $Ad(T)$ maps a twist from one frame to another.

- $ad(\xi)$ represents the commutator structure of se(3).

This is central in deriving manipulator Jacobians, rigid body dynamics, and state estimation on manifolds.